Would you pay $500 per month for your son to turn in his homework on time?

A growing number of parents are saying yes, according to a report this week in the Wall Street Journal. Following their viral 2021 report on the decline of men in higher education, the Journal has found that some parents of young boys are spending thousands per month on organizational tutors and coaches to combat this decline at the ground level. In exchange for their parents’ money, these boys receive tutoring in how to not forget homework, how to turn in assignments on time, and how to pay attention in class.

One might be forgiven for laughing, if it weren’t all so very lucrative. The fact that there is enough of a market for these services to survive, and that parents are paying as much for them each month as they might on a car payment, suggests this is not merely another strange news article.

Parents know, or at least sincerely believe, that without preventative measures their sons will suffer. Statistics vindicate their fear: Men today compose just 40 percent of enrolled college students, a historically low rate which might be even lower without the help of admissions practices that have been called “tacit affirmative action for boys.” In 2022, women earned nearly 58 percent of baccalaureate degrees, 62 percent of master’s degrees, and 54 percent of doctoral degrees.

The sea change in academia is by now sizable enough that one does not have to keep abreast of the latest reporting on the subject to know what is happening. A father may not know the male enrollment rates at his alma mater, but he can see his own son barely scraping through the same classes that his daughter seems to have no trouble with. A mother may never see the average grades of male and female undergraduate students, but she can guess correctly that the girls’ average is better.

There are many causes of this male decline to which we might point. One is the dangerous prevalence of technology in grade school today, which has long term effects on student focus. Another is the lingering effects of bad pandemic policies in school, and the bad habits they created. Yet these causes affect both boys and girls, albeit in different ways and to different degrees; there are still bigger factors at play.

Around the same time that men and women reached the egalitarian ideal of a 50–50 split between the sexes in earned undergraduate degrees, a radical shift was taking place in academic priorities. Feminists had long argued for an entirely new approach to education, one that would root out latent patriarchy, and this idea gained new traction towards the end of the century as a way to combat university decline. In their 1983 paper on the subject, feminist academics Marilyn Schuster and Susan Van Dyne argued that higher education needed a “curriculum transformation” in order to attract more females, since “attracting the woman student, the majority in the shrinking college applicant pool, and serving her well may be the keys for survival in the 90s.” This transformation, they argued, should result in a “woman-focused classroom,” which would be found both at women’s colleges and in the women’s studies departments of co-ed institutions. In this ideal, “women students are the overwhelming majority of the class…[and] the professor is a woman who exposes her class to a reflection of human experience that not only includes women but also draws attention to racial, cultural and class diversity.” It is no exaggeration to say this goal has been accomplished, and not just in the women’s studies wing of the university. Indeed, as we have seen, women are dominating in the majority of classrooms, with the exception of STEM programs.

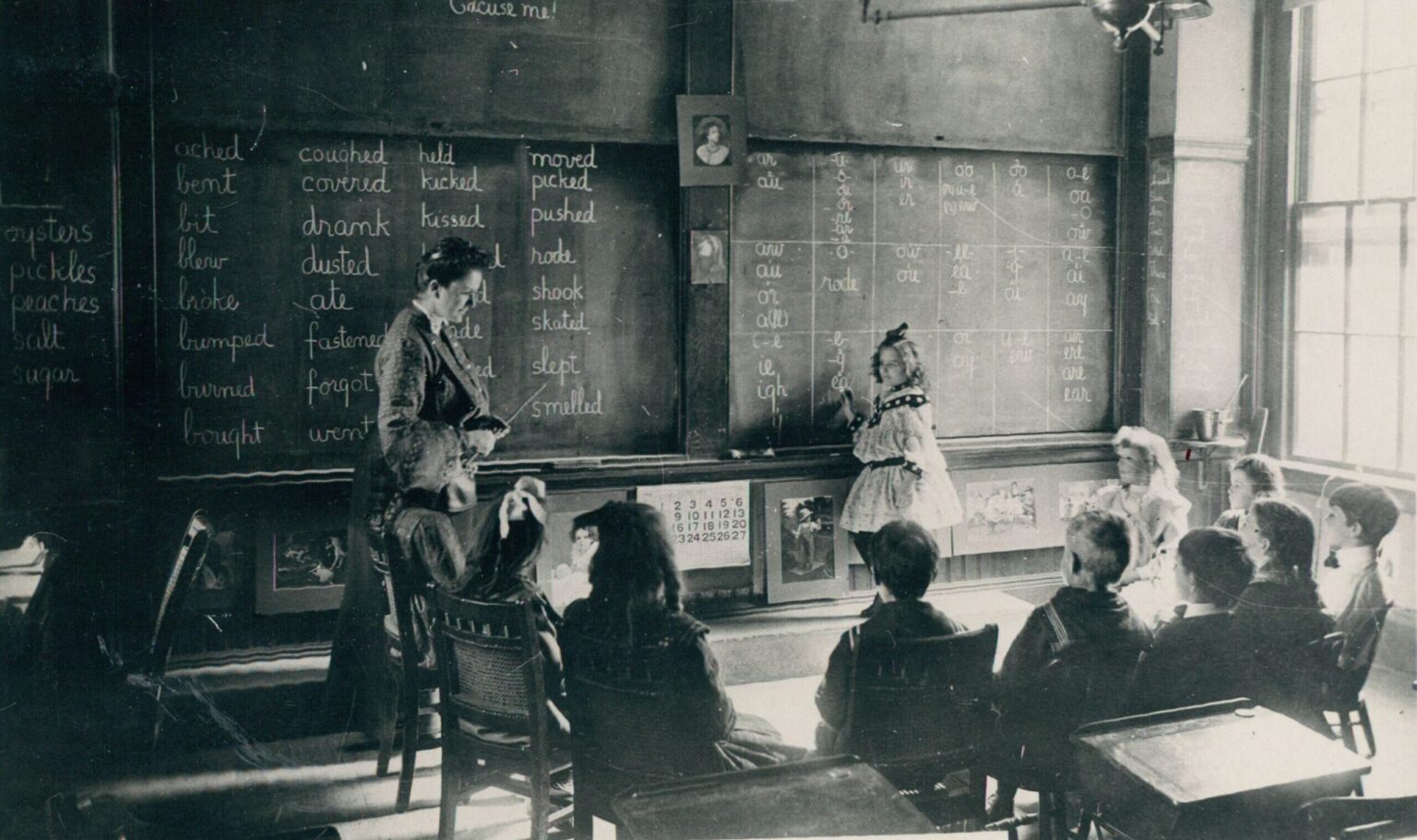

To chronicle these changes, where and how they were made, is the subject of books, not columns. Yet the result has been undeniable: The type of skills valued in the woman-focused classroom, those which are the primary measuring stick today, are qualitatively different from those in a male-focused classroom. Organization, timeliness, and assignments graded on completion have become the primary measure of a student’s ability, rather than a secondary one, as the woman-focused classroom rewards neatness over intelligence.

It is an unfortunate ailment of the modern mind that it seeks to equalize numbers wherever they can be found. The solution to a female-dominated classroom is not to make education more male again so we might find some magic midpoint. The solution, rather, is to consider how primary education might succeed in its purpose, which is education. At the root of this question is a need to recognize the fundamental differences between men and women, boys and girls.

In their paper, Schuster and Van Dyne glibly wrote that “whenever women enter the classroom, there’s sure to be trouble,” a reference to the well-documented negative impact on academic outcomes for students who are moved from single-sex to co-ed classrooms. Here is a dramatically simple solution, one which would go a long way in improving outcomes for both men and women, no organizational consultant required: Bring back the single-sex classroom.

Most women prefer this. They happen to learn better when they are not thinking about men. Men learn better, too, when they are not thinking about women, which comes as a surprise to no one. The fact that fewer consultants will make thousands by teaching your sons to conform to a female landscape is an added bonus.

Read the full article here