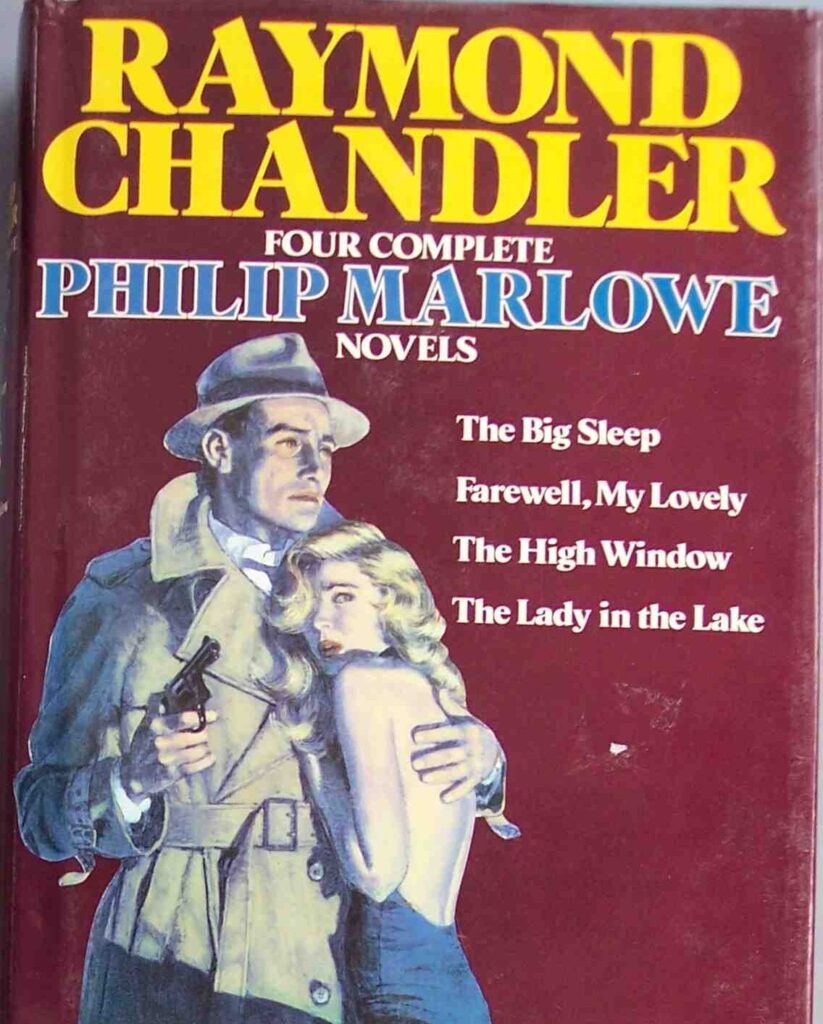

Crumbling on my bookshelves are most of Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe novels in editions brought out by Penguin Books in Britain in the early 1970s. Despite being priced in obsolete shillings and pence, long ago abolished by progress, the volumes are startlingly modern, their designs featuring 1930s lettering and cleverly colorized stills from Hollywood movies, mainly featuring Humphrey Bogart. I well remember being in love with them when they were new and I was a student Marxist, but I had not opened them for many years, fearing they would have staled on me. They have not.

This is surprising. I am an utterly different person from the red-shirted Trotskyist who bought these books in an utterly different England from the one I now inhabit. In the long years between, I have visited Los Angeles, wonderfully described by Chandler as “a big hard-boiled city with no more personality than a paper cup,” yet portrayed by him in such an alluring way. I have been lost on its freeways, afraid at one point that I might already be dead without knowing it and condemned, for my many sins, to drive along them forever in some kind of motorized version of Hell. And I have read Alison Lurie’s merciless portrayal of L.A. and its people in Nowhere City, in which the place itself is a concentrated solvent of marriages, morals and standards. I have completely changed my tastes in food, drink, music, literature, poetry, painting and architecture. But within seconds of beginning The Big Sleep, I was once again borne unresisting into Chandler’s California.

As before, I was left baffled by the actual plot. Normally this matters to me a great deal, and I am wary of books which are all about style but in which nothing much happens. Of course, a great deal happens in Chandlerville. Cops threaten, guns are waved, gorgeous dames sneer or tremble with mysterious horror, cars crash into the surf. Sinister persons arrive at Philip Marlowe’s seedy office. Threats are breathed down the telephone. Many drinks are taken, thousands of cigarettes are smoked, corpses appear or vanish, corruption flourishes in Bay City, and the filthy rich hide from the world in Idle Valley. Blackmail is a flourishing local industry, perhaps because in this age people had more secrets. There is a lot of chromium, there are many drugs, and the music in the nightclubs and gambling joints is mainly about sex. But the sex is both much more dangerous than we think it is today, and much more hidden. Pornography is present, and is denounced without irony, but not described. Homosexuality is mentioned but it is also disparaged, in a way which may one day get these books banned, or at least bowdlerized. Adultery and fornication are plainly taking place, but just offstage.

It is all fantastically modern, except that it is not quite. It is the modernity you used to be able to see in London up to about 1970, an old-fashioned future of streamlined trains and architecture, its finest symbol the Chrysler Building. This age was blotted out in Britain by the 1939 war and the destruction and poverty that followed it, but still survives in parts of the USA.

One of the things I love most about Chandler’s L.A. is that it contains streetcars and interurban railways, those forgotten features of American life now washed from public memory, much as enemies of the state were obliterated in Stalin’s Soviet Union. Not that Marlowe uses them much. If he cannot drive his beloved Oldsmobile, he would rather walk in the rain. But they can be seen, and heard a long way off, and here is rare evidence (it can also be spotted in the opening scenes of that great movie Double Indemnity) that the City of Angels has not always been a City of Cars.

Chandler’s description of weather also makes a dead city come back to life. The opening chapters of The Big Sleep are full of the rare approach of heavy rain, signaled by the way the hills behind the city look. And then the great cloudburst comes, and the cops are carrying pretty girls across the flooded street. I cannot help thinking that Chandler, with his (doubtless rainswept) English schooldays always in his memory, was comforted by the very occasional rain of his adopted home. But his descriptions of light and heat and above all of wind are extraordinarily evocative. Watch any film of a past event (take for example the easily found footage of Bob Dylan singing ‘Mr Tambourine Man’ at Newport in 1964), and it is when the wind blows and shakes the trees that the scene comes to life and the watcher (or reader) is fully involved in it. I have no idea why this should be so, but it is.

These, after more than 50 years, are the things I remember. So is the faintly socialist resentment of the very rich (who are almost always mean with the drinks, a major failing in Marloweville), and an occasional kindness towards the destitute. This kindness is what begins the whole strange saga of The Long Goodbye, in which Marlowe rescues a man down on his luck from the cops. It also features in Farewell My Lovely. To moments have stayed in my memory unchanged in five decades: Marlowe mailing cash in response to a sort of begging letter, after imagining, in detail, the lean, sad old man who has sent it; and an incident in which an elevator operator provides crucial help because Marlowe was once polite to him.

Ah, yes, the elevator operators, already being replaced by automatic push-buttons, but still very much in existence. I last encountered one of these in the stately Hotel Nacional in Havana, compelled by poverty to be a museum of outdated luxury. The concertina doors, the dark wood, the great brass lever, all survived by accident from the era of the Super Chief, and Guys and Dolls, thanks to Fidel Castro and John F. Kennedy, and the blockade against the modern world they constructed together in that city. The same hotel once gave me a “Silver Certificate” dollar bill in change, such as I had never seen before. Perhaps it also has hidden in its safe a $5,000 dollar ‘Portrait of Madison,’ such as Marlowe carried around for weeks. George Raft might have left it there, a long time ago.

I shall not try to list here all Chandler’s superb figures of speech. No modern English writer does them better. But the personal failure and unhappiness which lay beneath all this brilliance are very hard to bear, even when you know how good he could be. Chandler hinted at this overpowering sadness himself in what may have been his cleverest sentence, carved into his gravestone: “Dead men are heavier than broken hearts.”

Read the full article here