Wind, solar, and electric vehicles aren’t the clean energy accomplishments that many claim, climatologist David Legates says.

“The lithium, the atrium, all of the rare earth minerals that are necessary for the batteries, that are necessary for the solar panels, that are necessary for the wind turbines … are called rare earths,” Legates explains on “The Daily Signal Podcast.”

These rare earth minerals are acquired through strip mining, he says, a process that involves putting large chunks of earth into a solution. Once the minerals are extracted, what is left is a “toxic sludge lake.”

The process of strip mining changes the environment, adds Legates, a visiting fellow who serves on the Science Advisory Committee for the Center for Energy, Climate, and Environment at The Heritage Foundation. Legates, also a professor emeritus at the University of Delaware, is the author of a Heritage paper on rising sea levels.

Legates, who joins this episode of “The Daily Signal Podcast,” explains how wind turbines and solar panels are created and discusses his new book “Climate and Energy: The Case for Realism,” co-authored with E. Calvin Beisner. He also identifies what the cleanest form of energy really is.

Listen to the podcast below or read the lightly edited transcript:

Virginia Allen: Mr. Legates, welcome back to “The Daily Signal Podcast.”

David Legates: Thank you. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Allen: I’m really excited today to talk about your book “Climate and Energy: The Case for Realism.” Explain if you would, who is this book written for?

Legates: It’s written for people that are really interested in getting into some of the science, but not necessarily having your head held underwater with complete science discussion. So it’s more than just a cursory attempt at talking about climate. It’s much more detailed but not so detailed that you have to have a Ph.D. in physics to figure it all out.

Allen: What do you think are some of the most common misconceptions around the topic of climate change that you-all really try to tackle and address in this book?

Legates: Part of the issue is that carbon dioxide, we’re told that it’s a magic climate control. No. That essentially, if you put more carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide into the atmosphere, temperatures go up, you get more hurricanes, more tornadoes, more droughts, more floods, more all of the bad stuff that people don’t want to see.

And if we somehow kept carbon dioxide to a minimal level, somewhere between 350 parts per million to 286 parts per million, that life would be good. We wouldn’t have hurricanes, we wouldn’t have tornadoes. All these bad things would stop happening. Temperature would stop rising, the seas would stop rising, as [former President] Barack Obama said. And magic happens.

And the problem is it’s not connected directly to carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide is a bit player in all of this. So that I think is one of the take-home messages, is that carbon dioxide isn’t the climate control knob.

For most of climate history, we’ve actually seen that air temperature leads and carbon dioxide follows. And that makes total sense because when air temperature goes up, water becomes warmer. There’s more outgassing of carbon dioxide. And so as your temperature of the oceans rise, carbon dioxide is given off by the oceans, the atmospheric concentrations increase.

So generally, historically, we’ve seen temperature goes up, carbon dioxide follows. Now the question is, if carbon dioxide goes up, will temperature follow? And the answer is yes, slightly.

However, most of the absorption bands that we have with carbon dioxide are already saturated. So what that means is that, essentially, if you had no carbon dioxide or no greenhouse gases in the atmosphere at all, the addition of some makes a big deal. But as you start to add more and more and more, you get less of an impact. And so by the time we are where we are now, more carbon dioxide really doesn’t do a whole lot.

And so if we doubled carbon dioxide now, we get maybe a degree Celsius of warming and that would be it. And certainly it’s not worth the economic impacts that people want it to have.

Allen: This is really interesting. Probably the most common argument that I have heard, when you speak to folks who are very invested in the climate movement, climate justice, whatever you want to call it, the argument is that various things create more carbon emissions and cause the temperature to increase and that has negative effects. But you’re saying that, for one, it’s so minimal, and actually maybe is the opposite, the temperature is rising and then that increases the level of carbon emissions within the atmosphere.

Legates: Correct. The interesting thing, though, is when I got started in the late ’70s in this with climate change, climate change was global cooling. At that time we were told that global cooling would bring about more hurricanes, more tornadoes, more floods, more droughts, more of all the disasters.

So the question is, which is it? Is it warmer conditions bringing you more disasters or is it colder conditions bringing you more disasters? Or were we statistically somehow on a saddle point that said it was perfect at the time and if we went warmer or colder, both would get worse?

The answer is that if you look at the climate, what’s driving most of the storms and things that create variability is what we call the equator-to-pole temperature gradient. That is the how warm the equator is relative to the pole.

Now, if you have a very warm equator and a very cold pole, you have a lot of temperature contrast, and that brings about a lot of storminess. If in an extreme world where the pole and equator were at the same temperature, global circulation would actually stop.

So in a warmer world, the equator warms a little bit because it’s already warm, there’s a lot of water around and there’s a lot of water vapor in the atmosphere. And for a number of reasons, it takes a lot of more energy to raise the temperature of warm, moist air. But in polar regions, it’s very easy to warm the air with a little bit of energy input.

So a warmer world has a lessened equator-to-pole temperature gradient, which means the interactions of cold, dry air coming out of Northern Canada and warm, moist air coming out of the Gulf of Mexico, that contrast is diminished. That would diminish things like hurricane activity, that would diminish tornadoes.

So in reality, a warmer world is a less volatile weather world. And in particular, when we look at it with civilization, civilization has always done better under warmer conditions.

You develop a civilization when you’re not looking for food, clothing, shelter, and security. Very cold conditions, essentially, your quest for food, keeping yourself warm, it consumes all of your time. But when it’s warmer conditions, you have more food, you have more security, you have more the ability to take care of yourself more easily, and as a result, you have, therefore, more time to develop the arts, to develop technology, develop all the things we think about with civilization.

Allen: And correct me if I’m wrong, but what we’re seeing right now is not necessarily unique. We have seen these cycles of warming and cooling before?

Legates: Yes. In fact, that’s what we’ve had, was the Roman Warm Period, the Medieval Warm Period, the Modern Warm Period, was a Little Ice Age as well. So temperature has gone through cycles. Precipitation goes through cycles. We go through floods and droughts and back to floods again. Hurricane goes through cycles. The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, for example, means that in the 1970s we had a lot of hurricanes, then the ’80s, ’90s, and 2000s not so many. Then they started to come up again.

So almost everything runs through a series of cycles, and it’s because of this inconsistency associated with the planet. The idea is that we are not a linear system. We are a nonlinear system that brings about chaotic, unpredictable behavior in which higher order terms, which are difficult to predict, start to take over. That was what Ed Lorenz found when he was attempting to simulate a simple climate back in the ’60s.

And so that variability is built into the system. And it’s a lot of cases why we have El Nino, La Nina events, why we have the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, Pacific Decadal Oscillation, and so forth with things that just simply flip back and forth with apparently no forcing, but nevertheless, it’s because of the second order, higher order terms associated with climate.

Allen: One of the things in the book that you-all speak to and address specifically are sources of energy. Let’s take wind and solar first. There’s a lot of conversations around those and there’s a huge push toward wind and solar. What information did you-all discover and also put into the book in regard to those sources of energy?

Legates: Well, actually, what we found was not new. Everybody thinks wind and solar are clean, green, renewable—there’s no problem with it, it doesn’t produce any gases to the atmosphere. There are problems with it.

How do you get the lithium, the trillium, all of the rare earth minerals that are necessary for the batteries that are necessary for the solar panels, that are necessary for the wind turbines? Well, they are called rare earths not because necessarily they’re rare, but they don’t exist in seams like coal or copper and so forth. They exist sort of all over the place.

And the way you get them is strip mining. You … pick up a large chunk of earth, you put it into a solution where you get these rare earth materials to come out of solution, to solidify, so you can use them, but then you’re left with this big toxic sludge. And somebody’s got to go into the toxic sludge and pull these pieces out, and you have to keep doing this with the whole mountain.

This is why it’s strip mining. It changes the environment, that you have to completely go through it, and you get this toxic sludge lake that’s produced. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, they have a tendency to use child labor. Young children, 8, 10, 12, 14 are wandering through this toxic material, looking to pick up things in Southeast Asia. In a lot of places it’s done by slave labor.

So if you’re interested in social justice, these things are not very social justice-oriented. If you’re interested in environmental cleanliness, these things are not environmentally pure. It takes energy to do all this.

And the argument sometimes is the energy savings, or I should say the carbon dioxide savings, that you get by going to these sort of carbon dioxide-free energy sources. When you get the turbine and the solar panels, it takes more carbon dioxide to transport the energy, to extract the energy. It takes more nonclean and green energy to get them out than it’s going to produce.

So like I said, at the end of the day, we’re all told it’s clean and green because you see it’s spinning there or you see the panel sitting there, it’s not producing gases. But to get to that stage, there has been an awful lot of disastrous and environmental and social efforts that have gone on behind the scenes.

Allen: What about car batteries for electric vehicles, like in a Tesla? How does that compare to powering your car with gas?

Legates: Well, that’s the other issue. … And we have this in Delaware. We’ve got an EV mandate that’s been put on us and we’re trying to fight back against us. But part of the issue is that to produce the batteries, they require these rare earth minerals, and as a result, you’ve got to go through the same process to build the batteries.

Second of all, I think I saw somewhere it takes an inordinate amount—I can’t remember offhand how much—it takes an inordinate amount of strip mining to get just one car battery.

The second problem is … where does the energy come from to power the battery? So if you’re using fossil fuels to power, to generate the electricity to load the battery, the problem then becomes how much are you using and are we still producing carbon dioxide? And therefore, your clean and green car really isn’t clean and green after all.

The other problem is, what happens if you’re in an accident? First responders are finding out that the batteries aren’t in the same place in every car. The power connections aren’t in the same place. With gasoline or diesel, it’s easy, you put water on it, you mitigate it, that’ll put out the fire. Lithium fires will burn effectively for long time periods and you can’t cool them down. I mean, essentially, as you remove the water, lithium will immediately fire up again in contact with the atmosphere. And so you get these very hot flames that can’t be extinguished.

The other problem they’re running into is, you get to an accident, the person’s hurt. You’ve got to use the jaws of life to go in. If the jaws of life happened to connect the battery or any wire connecting the battery, you now light everything up. The person in the car can be killed, the first responder can be killed.

That’s not usually a problem with gasoline cars. That’s definitely a problem with electric vehicles.

And the final thing is we’re finding, under very cold conditions, they don’t run well. We saw in Chicago, and for example, batteries just don’t hold the charge as long.

In a case in Delaware, we’re requiring all school buses to go to electric vehicle school buses, and one of the weird things about it is they can’t recharge them fast enough. So the school bus agencies are saying, if we’re going to take kids to school and then bring them home, we’ve got to have two buses to do that. Because taking them to school and bringing them back, there’s not enough time to recharge them before we have to take them home. So we’ve got to double the number of buses we have in our fleet.

It’s just continuously an added expense.

Even in Delaware, we’ve got now a requirement: If you build a new house, you have to have a connection for an electric vehicle inside that house, whether you have an electric vehicle or not. If you build a new apartment complex, each apartment complex, depending on its size, has to have a place outside that’s not on the street to park a car and recharge the electric vehicle.

So to build a house, to build an apartment complex is far more expensive now, simply because you’ve got to build in the infrastructure to actually have an electric vehicle recharged, even though nobody in the house or nobody in the apartment complex actually has an electric vehicle.

Allen: I find it really fascinating that you-all, in the book, link sources of energy with economic stability in a region. Explain how the sources of energy that we choose to use have an effect on the poverty of an area or its potential success.

Legates: Well, that’s part of the issue, is that one of the things that’s brought people out of poverty has been technology, and what’s been driving technology has been the availability of inexpensive energy.

I mean, in the 1800, you had approximately 10% of the population of the planet above the poverty line. In 2020, you have approximately 90% of the population above the poverty line. How did that happen? That happened because of technological developments. But in order to make technology go, you had to have inexpensive energy. If energy is really expensive, then you can’t use the technology you’ve developed, or I should say only the very rich can get access to it. The poor can’t. By making energy inexpensive, which is one of the things fossil fuels have been able to do, then everybody has access to energy and therefore, they have access to the technology.

See, before that, we had to rely on beasts of the field to get excess energy, slavery because you have to have somebody to do the work, or you had to, effectively, as we moved into first of all, is to use whaling because whale oil could be used.

And when petroleum came along, the need for slavery was nonexistent—although people will still do it because it’s ingrained in human society. But slavery, the need for slavery as cheap labor goes away, the need for whale oil goes away, the need to use animals goes away, and essentially we were able to develop quite a bit, and the benefit was to bring most of the world out of poverty.

Allen: So if you were giving a prescription to say, “All right, we should start relying most heavily on this form of energy and this form of energy,” what is the tried and true, most successful, cleanest forms of energy that would be most cost-efficient and not harmful to our environment?

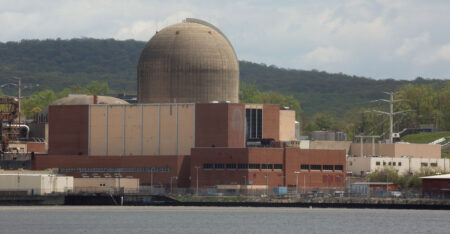

Legates: Nuclear. Nuclear is probably the future and should have been the present. There were issues in the United States, why it didn’t happen. Three Mile Island at the same time the movie “The China Syndrome” came out sort of put a kibosh on it.

But if you look at France, for example, much of it runs under nuclear. It has a much smaller spatial footprint, which allows you to have more land for development, but more land for animals to live on, more land for agriculture.

I mean you look now, what we’re doing in Delaware, for example, is we’re converting agricultural farmland over to solar factories. So we’re taking land out of agriculture and putting in solar panels all over the place. They’re doing the same thing, for example, in Iowa. One of the things you’re seeing is that corn that’s produced is going to biofuels and ethanol. Well, that could have been food that could have been feeding people.

So with nuclear, not only is it fairly safe—I mean, we can argue this point, but I think most people argue that nuclear is as safe as anything going, particularly with modern nuclear that we have, and in particular, it has a much smaller spatial footprint, so you can get the same amount of energy over a smaller area. It doesn’t require as much space. So there’s more space left for producing food, for allowing nature to exist in the way in which it did before, to allow people to expand. It’s probably where we should have been all along.

Allen: The book is “Climate and Energy: The Case for Realism.” Mr. Legates, if there are one or two things that you would like readers to take from this book, what is that?

Legates: The title: “Climate … The Case for Realism.” Climate change always happens. Climate change has always happened and it will always happen. Don’t get caught up in the question that we’ve got to stop climate change, it’s like trying to stop the sun from rising. It’s never going to happen.

There’s never been a condition in the planet that the temperature, that the precipitation has always remained constant. It’s always been variable. And so when you’re told that we’re going to get more hurricanes, more of this, more of that, that’s all not going to happen. We go through cycles, as you mentioned. We go through different characteristics. And as things change, things stay the same in a sense.

So we’re going to see variability, we’re going to see change, but climate is variable. Climate changes and that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

Allen: Excellent. The book, again, is “Climate and Energy: The Case for Realism.” You can pick up a copy today.

Read the full article here