On the night of August 20, 2023, my 79-year-old mother, after a lifetime of good health, was told that she had metastatic breast cancer. I sat with her in the emergency department, where she had gone most reluctantly after a series of strange symptoms that appeared intermittently over the summer: pain in her neck and back, fatigue, and, most alarmingly, lightheadedness that had led to falls—something entirely out of the ordinary for my active, youthful, elegant mother, who always looked her best for a social occasion and who led a life free of vice. She never lit a cigarette, avoided prescription medication, believed in the salutary effects of fresh air and exercise, and seldom indulged in anything more than a glass of wine. She usually drank milk with dinner.

Yet here we waited in a dark, dingy room past midnight. Scans were taken, blood tests were administered, and doctors migrated in and out. At some point, it was determined that there were lytic lesions on my mother’s spine—apparently the cause of her unsteadiness over the summer—that were suspected to be signs of multiple myeloma, a diagnosis so crazy-sounding, so out-of-the-blue, that it was easy to block out as more tests were done. Finally, one last glum, weary doctor gave what turned out to be the conclusive diagnosis. My dear mother had breast cancer that had spread to her spine, her ribcage, her lungs.

Such a diagnosis—its gravity, its sweep—is overwhelming in and of itself, but, in those awful wee hours, I immediately saw that we had crossed the Rubicon in another way. My mother’s life was soon to be overtaken by more than just the disease. Upon being admitted to the hospital, she was absorbed into something she had managed, through good genes and good fortune, to avoid her entire life: a health care apparatus that does not merely aim to treat disease but to take over of the person herself.

My mother was in the hospital for about five weeks before the cancer overwhelmed her. She passed away on September 28. During that time, my mother felt that her views, beliefs, and wishes had become subject to physicians who could read a scan but not her soul. She came to feel not only that her health had failed her but her self-governance had been taken from her, too. She was bewildered by the barrage of medical terminology, jargon, and psychobabble that was being presented to her—less to enable her decision-making, she felt, than as a courtesy. That she would consent to, or at least play along with, whatever treatments or procedures were being proposed seemed to be regarded as a given by the confident, condescending medical professionals. When she had questions, doubts, or second thoughts about the proposed course, most of the doctors seemed surprised, perplexed, and sometimes visibly annoyed.

In our medically oriented society, thou shalt not question the men in the white coats. Our fear of disease has normalized such insane things as beaming radiation into our bodies (so-called “radiation therapy”) or allowing ourselves to be injected with poison (so-called “chemo”). Even if these treatments can be justified, they should never be considered normal—and my mother certainly did not think of them as such as they were being presented to her. Appointments were made for her without her even being asked; her calendar would have to take a backseat to whatever the men in the white coats had in mind.

Yes, my mother ultimately decided what to do or not to do—and she did agree to a surgery—but only after she had been lectured at and talked down to. Every instinct in her told her to simply go home, and she did so twice during the ordeal. By then, she was too weakened to remain there. While I recognize that the cancer itself left her in this state, I can say without equivocation that it was the health care system that made her feel trapped, cornered, no longer in control of her life.

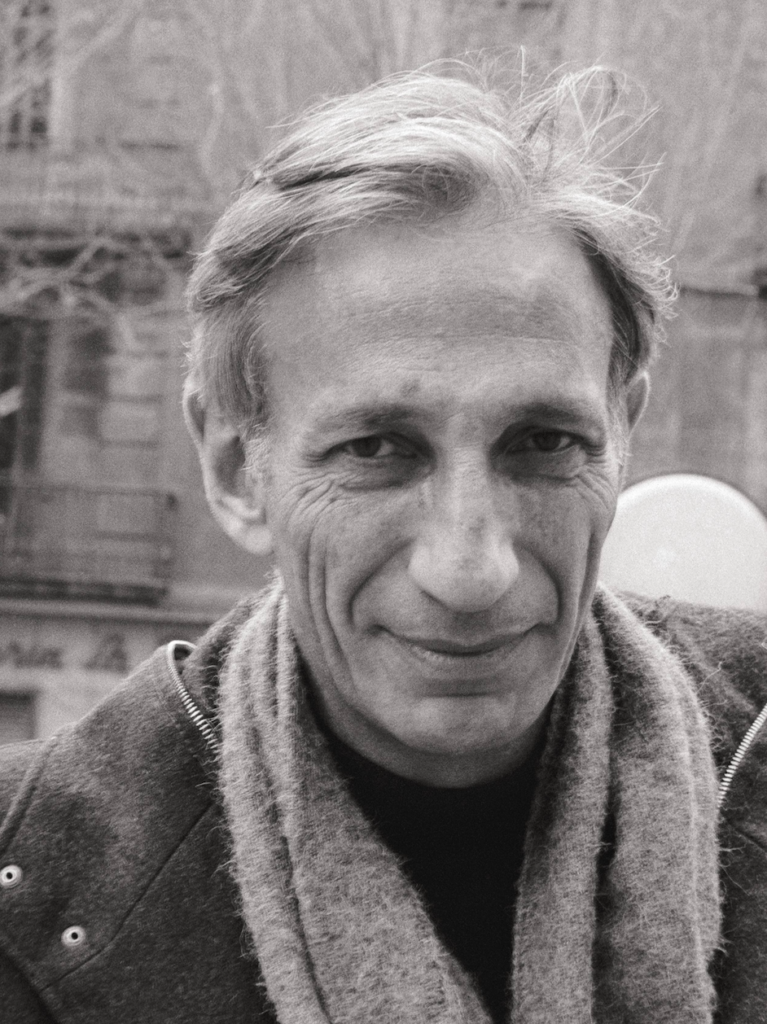

The pressure with which my mother was encouraged to accept her disease as a kind of god and her doctors, by virtue of their purported knowledge and alleged mastery of the disease, as ministers of sorts reminded me of the writings of Ivan Illich, one of the most brilliantly contrarian and invigoratingly humane thinkers of the last century.

Born in Vienna in 1926, Illich trained at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome and, in 1951, became a Roman Catholic priest. Various assignments followed, including in Washington Heights and as vice rector of the Pontifical Catholic University of Puerto Rico. He seems to have been too obstinate and headstrong for clerical life, so in the late 1960s he moved on from the priesthood. During the ensuing decade, he came to widespread attention in the secular press for a series of books that chipped away at conventional wisdom on a variety of urgent topics, including Deschooling Society (1971), which is often thought of as a companion piece to Paul Goodman’s Growing Up Absurd (1960); Tools for Conviviality (1973); and Medical Nemesis (1975). Illich died in 2002.

It was the last book that I read, under its new title Limits to Medicine: The Expropriation of Health, during the dying days of the government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Having just witnessed all strands of society—religious, civic, and commercial—made subservient to the irrational edicts of a public-health establishment that considered itself beyond reproach, I was sympathetic to Illich’s basic argument: health care in this country has evolved from a feature of life, like going to the dentist for a toothache, into a lifestyle all its own. “Previously modern medicine controlled only a limited market; now this market has lost all boundaries,” Illich writes, in his typically florid and righteous prose. “Unsick people have come to depend on professional care for the sake of their future health.”

Illich writes that ever greater numbers of people want doctors to be more than just doctors. They must be lawyers and priests, too. “As a lawyer, the doctor exempts the patient from his normal duties and enables him to cash in on the insurance fund he was forced to build,” Illich writes. “As a priest, [the doctor] becomes the patient’s accomplice in creating the myth that he is an innocent victim of biological mechanisms rather than a lazy, greedy, or envious deserter of a social struggle for control over the tools of production.” The “giving and receiving of therapy” becomes embedded in life, and “access to treatment” turns into a political cause.

Illich is greatly exercised by what he regards as the essential ineffectiveness of what he calls “medical utopia,” and he cites the ebb and flow of various infectious diseases through history as proof: tuberculosis was once a terrible killer, then it wasn’t; cholera, dysentery, and typhoid were once much feared, then they weren’t; scarlet fever, diphtheria, whooping cough and measles once wreaked havoc, then they didn’t. These things happened “outside the physician’s control,” Illich contends.

“In part this recession may be attributed to improved housing and to a decrease in the virulence of micro-organisms, but by far the most important factor was a higher host-resistance due to better nutrition,” writes Illich, who also credits improved hygienic measures that fall somewhat outside our usual definition of “medicine” such as water and sewage treatment and “the use of soap and scissors by midwives.” Medical historians are free to take issue with the specifics of Illich’s arguments, but anyone who lived through the Covid-19 pandemic and witnessed, in real time, the futility of public-health interventions in the face of a virus that eventually infected everyone and quickly lost its bite will recognize the truth in his instincts.

Illich is on more provocative ground when he argues that modern medicine actively induces harm. “Clinical iatrogenic disease comprises all clinical conditions for which remedies, physicians, or hospitals are the pathogens, or ‘sickening’ agents,” he writes, pointing, quite reasonably, to superinfections brought about by antibiotics, unnecessary surgery, and plain and simple malpractice. “Doctor-inflicted pain and infirmity have always been a part of medical practice,” he writes. It is fair to point out that Illich’s data is over half a century old and his conclusions have a hint of cherry-picking. At one point, he insists that Boy Scout training, good Samaritan laws, and ubiquitous first aid equipment are better answers to car accidents than “helicopter-ambulances”—a debatable, if appealingly contrarian, assertion. All the same, the recent rise in awareness of vaccine injuries and prescription-drug side effects more generally lend credibility to his position.

Illich’s diagnosis is most deadly accurate when he sets his sights on the health care establishment’s takeover of life itself. Modern society lets us opt out of nearly anything—religion, marriage, children—but tries its best not to let us opt out of health care. “Lifelong medical supervision . . . turns life into a series of periods of risks, each calling for tutelage of a special kind,” Illich writes, adding, “For rich and poor, life is turned into a pilgrimage through check-ups and clinics back to the ward where it started. Life is thus reduced to a ‘span,’ to a statistical phenomenon which, for better or for worse, must be institutionally planned and shaped.” He objects to diagnostic tests for making people unnaturally riddled with anxiety and alienating them from the ranks of “the normal and healthy,” and he abhors the arrogance of medical personnel tending to terminal patients: “At a cost of between $500 and $2,000 per day, celebrants in white and blue envelop what remains of the patient in antiseptic smells.”

Of course, illness and death are promises made to us in the aftermath of the Fall; we can never evade them. This is the truth Woody Allen clumsily perceived when, in Hannah and Her Sisters, his character leapt with joy when he found he didn’t have a brain tumor but came back down to earth when he realized that something would, one day, fell him. “The major religions reinforce resignation to misfortune and offer a rationale, a style, and a community setting in which suffering can become a dignified performance,” Illich writes. It is the crowding-out of such an understanding of suffering that most clearly outrages him. The nullification of pain is itself a sin, Illich writes, since, in the past, “pain was man’s experience of a marred universe, not a mechanical dysfunction in one of its subsystems.”

In my own recent experience, I found that the health care apparatus advances a secular religion all its own. (In his book, Illich calls the hospital “the modern cathedral.”) In this paradigm, the utter irrelevancy of actual religion was made plain to me that first night in the emergency department. After we arrived, I was for a time separated from my mother, and while I was waiting I was greeted by a woman who identified herself as a chaplain. To which faith she belonged was not disclosed, but then that seemed to me the whole point of such hospital chaplains. Assuming that the worried visitors of the patient have no priest, pastor, or rabbi of their own, the hospital would furnish one who could offer succor in the blandest, least doctrinal terms. Perhaps I resented the assumption because I also knew it to be true: at that moment in our lives, we had no religious adviser to call upon. We were, literally, at the hospital’s mercy.

My wonderful and sorrowfully missed mother never read Ivan Illich, but she spent her entire life assiduously avoiding the state of affairs he described. As she told nearly every doctor she encountered, she had twice before been in a hospital—to give birth to her two sons, my brother and me. (In fact, she had been admitted on one other occasion: In 1969, when she was in her mid-twenties, she had undergone a minor surgical procedure because she suffered from hay fever.) Instead, she trusted in God, her good habits, and her robust family history—her mother lived to 100. For 79 years, she managed to live a life that was not reduced, as Illich would put it, to a “span” that was to be “institutionally planned and shaped.” She would rather, as she said to me, take her chances—as she did during Covid, which she survived without a vaccine and only wearing a mask when forced to by a store. Better that than to be ruled by doctors.

In the aftermath of my mother’s death, I received a generic sympathy card from the chaplaincy program at the hospital. The emptiness that missive inspired is hard to overstate. The only thing that has nourished my soul and quieted my spirit has been attending church services, which I have been doing regularly since Christmas Eve. Ivan Illich was right: a man in a white coat is a poor, pitiful substitute for a hymn, a Gospel reading, and a prayer.

Read the full article here