Since the 2020 election, President Joe Biden has made clear his intention to drive America’s gasoline- and diesel-powered cars and trucks right off our roads. In May, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed a new rule that would impose such strict emissions limits that carmakers would only be able to comply with them by switching the vast majority of their production to electric vehicles by 2027.

The EPA estimates that under its new rule, nearly 70% of all new cars and trucks produced in America would be fully electric by 2032.

But the proposed rule is based on a flawed interpretation of the Clean Air Act. The act gives the EPA the authority to regulate air pollutants from vehicles, but not to dictate what types of vehicles consumers can own. It requires the EPA to set emissions standards that allow manufacturers enough time “to permit the development and application of the requisite technology, giving appropriate consideration to the cost of compliance within such period.”

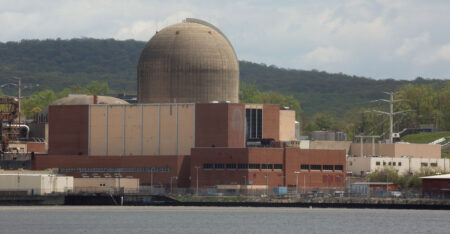

The proposed rule would have negligible environmental benefits but enormous economic and social costs. It would increase electricity demand and strain the electric grid, while annihilating funding for building and maintaining highways, which is derived almost entirely from taxes on gasoline and diesel.

It would harm consumers by taking away their right to decide what kind of vehicle to buy. Low-income and rural Americans in particular would face higher transportation costs and reduced mobility options. The new rule would also undermine U.S. competitiveness internationally and national security by making us more dependent on foreign sources of critical minerals and batteries for EVs.

The proposed rule is not only bad policy, it is also “arbitrary and capricious” because the Clean Air Act does not authorize the EPA to force a transition to EVs.

The proposed rule’s legal problems start with its definition of the “class or classes of vehicles” to which the emissions would apply. In order to kill off gasoline-powered cars, the EPA is defining the relevant classes as vehicles of various sizes that include both gasoline- and diesel-powered vehicles as well as electric vehicles of those sizes.

The phrase “class or classes of new motor vehicles” cannot mean just whatever the EPA wants it to mean. The phrase could not, for example, include both electric scooters and gasoline-powered cars under the same emission standard, even though both are “motor vehicles” under the Clean Air Act. Common sense dictates that the act cannot be read as authorizing the EPA to force car manufacturers to produce electric scooters instead of cars in order to comply with emissions standards for cars.

As I explained in The Wall Street Journal last summer, the Supreme Court recently struck down a similar attempt by the EPA to regulate power plants under the Clean Air Act in West Virginia v. EPA. The Supreme Court observed in that case that the EPA’s 2015 Clean Power Plan would have “resulted in numerical emissions ceilings so strict that no existing coal plant would have been able to achieve them without engaging in [generation-shifting].”

The court went on to note:

Rather than focus on improving the performance of individual sources, it would improve the overall power system by lowering the carbon intensity of power generation. And it would do that by forcing a shift throughout the power grid from one type of energy source to another. … There is little reason to think Congress assigned such decisions to the Agency. … We presume that Congress intends to make major policy decisions itself, not leave those decisions to agencies.

The same may be said of the EPA’s attempt to kill traditional cars and trucks. Its emissions limits are so strict that no manufacturer of combustion engine vehicles will be able to comply with them, except by switching to the production of a completely different type of vehicle. The switch from traditional cars to EVs is the definition of a major policy decision, and nowhere in the Clean Air Act does it say that Congress wanted the EPA to make the choice of where, how, and when that switch should happen.

The EPA’s new proposed standards build on a 2021 EPA rule that significantly tightened emissions standards for vehicles starting with model year 2023. Most auto manufacturers had already completed their design cycle for their 2023 models by the time the rule was promulgated. The 2021 rule is currently being challenged in federal court by a coalition of states and stakeholders in the case of Texas v. EPA. That case will likely decide the fate of this newly proposed rule as well.

No agency has come closer to claiming virtually totalitarian powers to reshape American society as the EPA has. The sooner federal courts rein in the runaway EPA, the better for everyone.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email letters@DailySignal.com, and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the URL or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.

Read the full article here