We recently looked at the amazing power of global warming to alter time itself. That rather dubious claim raised a number of eyebrows among our readers for obvious reasons. Now the subject of time is making headlines again for a different reason. It’s being claimed that time passes differently on the moon, with a day lasting nearly sixty microseconds less than on Earth. This is apparently messing up some of NASA’s calculations for moon missions and communications. So the White House has directed NASA to work with other international agencies and come up with “a new moon-centric time reference system.” In other words, we’re being told that we need a new moon clock. If you find yourself wondering why time doesn’t pass at the same rate everywhere, you’re not alone. But I suppose NASA needed something to keep themselves busy in between SpaceX launches. (Associated Press)

NASA wants to come up with an out-of-this-world way to keep track of time, putting the moon on its own souped-up clock.

It’s not quite a time zone like those on Earth, but an entire frame of time reference for the moon. Because there’s less gravity on the moon, time there moves a tad quicker — 58.7 microseconds every day — compared to Earth. So the White House Tuesday instructed NASA and other U.S agencies to work with international agencies to come up with a new moon-centric time reference system.

“An atomic clock on the moon will tick at a different rate than a clock on Earth,” said Kevin Coggins, NASA’s top communications and navigation official. “It makes sense that when you go to another body, like the moon or Mars that each one gets its own heartbeat.”

Time shouldn’t be able to behave strangely, and for the most part, it doesn’t. If you are hanging out in Chicago and your sibling is relaxing in Perth, Australia, time passes the same way for both of you at a rate of one second per second. It doesn’t matter what the local clocks say because time zones are artificial demarcations created by humans.

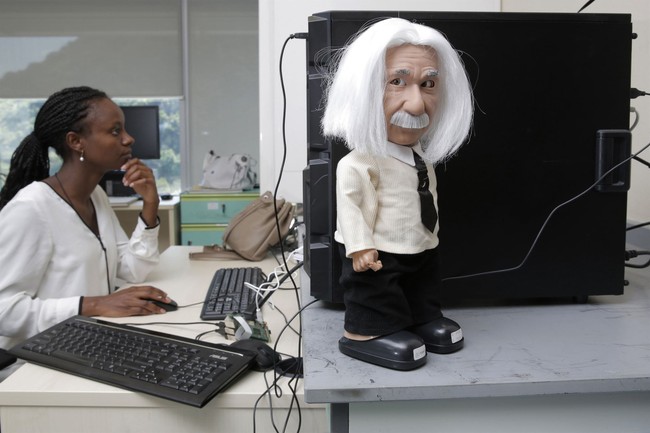

But at least in theory, that’s only true if you and your sibling are traveling at the same speed. Time is supposedly relative based on the motion of the observer. Einstein cooked up that concept when developing his theory of relativity. He described the twin paradox, where one brother travels to another planet at nearly the speed of light and returns while his twin brother remains on Earth. Upon his return, the traveling brother is significantly younger than his sibling. For an example closer to home, NASA conducted an experiment using twin brothers Mark and Scott Kelly. Scott spent a year orbiting the Earth onboard the ISS traveling at roughly 17,000 miles per hour while Mark stayed home on the planet. Upon his return, Scott was supposedly younger than his brother, though only by a tiny fraction of a second.

This effect can allegedly be demonstrated if you have an atomic clock at Mission Control in Houston and another one on the moon. The clock on the moon will advance ever so slightly quicker than the one on Earth. That roughly sixty microsecond-per-day difference adds up after a while and can mess up NASA’s control systems during missions. But does that mean that time itself is actually passing more quickly on the moon or do we just need better clocks that can adjust as required?

I’m not going to pretend to know the answer to that question, though I find the question fascinating. Atomic clocks are reportedly accurate and reliable to an incredible degree, so if they behave differently on the moon, perhaps relativity in that regard is real. But it just doesn’t “feel” as if time can pass at different rates in different places. The entire concept of time and how it passes is just man’s explanation for why everything doesn’t happen at once. It’s one aspect of physical reality. Why would it be flexible? I would attempt to put up an argument here in response, but even I lack the amount of hubris required to claim that I’m smarter than Einstein. (Even though he and his family clearly never figured out that “i before e except after c” rule.)

Read the full article here